A Life Steeped in History

by Ruth Graham

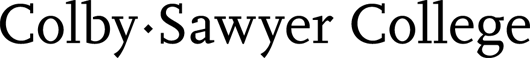

“I Feature really enjoy teaching,” says Professor Emerita Hilary Cleveland, sitting in her sunny living room in New London. “I found that out five years into teaching, and never wanted to do anything else.” It's easy to believe her: Cleveland spent 57 years teaching history and political science at Colby-Sawyer, retiring in December at 84.

Cleveland didn't set out for a career in teaching, or for a life spent in one small New Hampshire town. She grew up in New Jersey and Andover, N.H., graduated from Vassar College, and then traveled to Geneva, Switzerland, for further study at the Institute of International Relations. “I wanted to be a diplomat,” she says, explaining that her dream had always been to serve in an ambassadorial role in a far-flung nation. “I certainly didn't expect to live in New London, New Hampshire, or to teach.” But meeting her husband changed her plans.

The roots of James Colgate Cleveland's family tree are entwined so deeply with those of New London and Colby-Sawyer that it's difficult to tell them apart. The names Colby, Colgate and Cleveland emblazoned on various buildings on campus all appear in the family's history, starting with New Hampshire governor Anthony Colby (1792-1873), who was born in New London and lived in the Colby Homestead on Main Street. Several generations later, Cleveland's parents moved into the homestead and gave Hilary and her husband the house she lives in now, just down the road. When her husband's parents died, Colby Homestead went to the college, which currently uses it to house the Office of Advancement. The property's barns became the Susan Colgate Cleveland Library/ Learning Center.

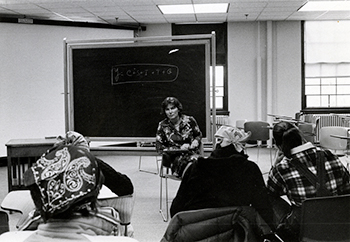

James and Hilary met in the summer of 1950, and married at the end of the year. They lived in the house on Main Street until James was sent to Germany during the Korean War. They left as newlyweds who only used a few rooms in the house, and returned to the house as parents. They eventually had five children. James, a moderate Republican, served in the New Hampshire Senate between 1951 and 1963, and then ran successfully for U.S. Congress, where he held his seat until he retired in 1980. He died in 1995.

After settling back in New London, Cleveland got the idea that she'd like to try her hand at teaching. When she first inquired, Colby Junior College (as Colby-Sawyer was then known) had no room for her, but she helped Professor James D. Squires with his work on a history of New London, and eventually he hired her.

“In those days, there were six teaching days,” Cleveland recalls. Classes were held Monday, Wednesday and Friday, or Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday mornings. When Cleveland began teaching, she was given five courses to teach during the sixday weeks—an unimaginable teaching load these days. That first semester she taught classes including international relations, European history, American government and comparative government.

“I had never taught,” Cleveland remembers with a laugh. “The first class—this is typical of any teacher—I had all my notes written out in desperation. They were 50-minute classes, and I figured it would take 45 or 50 minutes with discussion.” Instead, overcome with nerves, she raced through her presentation in 30 minutes flat, and no one had any questions to help her prolong it. “It was a disaster!”

By necessity, her teaching style quickly evolved to incorporate more class discussion than traditional lectures. With such a heavy course load, “it was just foolish to try to know everything,” she explains. “My teaching style is much more throwing out topics and giving some background to it, and getting the students involved.” Early on, Cleveland got into the habit of rising at 3 a.m. to prepare for classes, a habit she keeps to this day.

No matter the subject, she wanted her students to be able to make connections between history and current events. “Everything is connected, and if you can get the students to see that, you've done your homework,” she says, using the example of how current issues in Iran can be traced back to the country's colonial era. “They don't remember a lot of facts and dates, and neither do I. So why emphasize those?” Her favorite classes to teach have been the ones in which she learned. A course on Far Eastern history, which pushed her to delve into Chinese and Japanese culture and history, remains one of the most memorable for her.

The school's campus has changed significantly since her arrival, too. Students used to eat in Colgate Hall, she recalls, and there was no Sawyer Fine Arts Center, no Baird Center, no Ivey or Reichhold buildings. The campus then was charming and small, essentially just Colgate Hall and a circle of dorms.

Cleveland says she misses some of the old routines on campus. Back when students attended a mandatory chapel service at First Baptist Church on Main Street, most of the faculty would gather in a “butt room” in the basement of Colgate to have coffee, pick up their mail, and chat with each other. Nowadays, most departments have their own administrative assistant and coffee area. “I don't know the teachers in the art department or exercise and sport sciences department,” Cleveland says. “The only people I know in the college are the people in my own department. It's a shame. You lose a collegial atmosphere.”

Cleveland's niece Page Paterson led the charge to end that mandatory chapel requirement in the 1960s, a time of many other significant changes to campus culture. It was a time of protest and unrest at many campuses across the nation, and institutions were engaged not just with issues of national importance like the Vietnam War, but with the question of whether colleges had the right to act in loco parentis—in the place of a parent.

In the 1950s, students had curfews every night. Each dorm had a faculty resident who kept tabs on students, and required they get their parents' permission to go out of town. Only seniors were allowed to have cars, and only in the spring term. The all-female student body had a dress code that included skirts, sweaters and Colby Junior College blazers, which they wore with knee-length socks and moccasins or Oxford shoes. “Students came to class looking very proper and usually very neat,” Cleveland says. By contrast, students in her morning classes in recent years often arrived wearing pajamas, topped with a parka in winter.

Cleveland isn't sentimental about the restricted lives of young people, particularly women, in the 1950s. Many women were sent to the two-year junior college, as opposed to a four-year institution, because their parents didn't see the point in sending a young woman to school for so long. Bachelors' degrees were for young men, while young women should finish in two years and “then go off and be a secretary or get married.” The positive side of that, she notes, was that Colby Junior College attracted many brilliant women who nowadays would likely head to the Ivy League.

At the same time, however, she sees students today struggling with the broad range of freedoms they have been granted. “There seem to be more students who are psychologically upset at Colby-Sawyer now, given all of these freedoms and then some of the bad results,” she says. “Some 17- and 18-year-olds are just not equipped to handle it.” Academically, things haven't changed quite as much. “I've always had some excellent students, some very poor students, and the large majority, from the beginning to now, are 'medium' students, but ready to be awakened,” she says.

Cleveland has worked under all eight of the college's presidents, starting with H. Leslie Sawyer, who was in his final year of leadership when she began teaching in 1955. She admired Eugene Austin, president from 1955 to 1962, who involved Colby Junior College students in the wider world by hosting forums on current events. (“In those days he could require the students to attend, so they were pretty well attended,” Cleveland says wryly.) She has warm memories of many other administrators, particularly an early dean and English professor named Eleanor Dodd. “The dean had very little praise for anyone, and when she said, 'Good job,' or 'I like that,' it just meant all the world because she was chary with her praise,” Cleveland recalls. “She had very high standards for faculty, so I admired her tremendously.”

The town of New London has evolved since Cleveland arrived. Then, about 1,300 people lived in New London, though the population swelled in the summer with the arrival of visitors from Washington and Philadelphia who traveled north to escape the heat. “What I see is much more sophistication in New London,” she says now. “It's not a little farm town anymore.”

Despite her busy teaching schedule, Cleveland always made time for public service. She campaigned for her husband's political career, but she also served as New London's town moderator for many years, and accepted an appointment by President George H.W. Bush to serve on the International Joint Commission, a body that helps Canada and the United States negotiate boundary water disputes. When she switched her allegiance to the Democratic Party in 2004, the news made national headlines. This year, she is supporting President Obama and New Hampshire gubernatorial candidate Maggie Hassan.

Cleveland officially retired in 1991, but she continued teaching classes until December of last year, which she considers her real retirement. Did she expect to be at it this long? “Oh, good heavens, no,” she says with a laugh. “I didn't expect to live this long!” She says she kept teaching for so long for a simple reason: She loved it. “I know some people don't and they can hardly wait for retirement,” she explains. “But I happen to like students, and I happen to like their different backgrounds and points of view. I love thinking that maybe they're getting interested.” Once in a while she received letters from former students saying that her classes inspired them to be curious about history or government for the first time, and those letters kept her going.

Even in retirement, Cleveland remains active and connected to the college. She's involved with the adult-education program Adventures in Learning, which she helped to found. With the help of a student intern, she is also beginning to organize and box up her papers, which she will donate to the library named for her husband's family. Always self-deprecating, she calls the papers “junk.” But for Colby- Sawyer, Cleveland's papers—and memories— are an invaluable record of many decades of history.