Make a Joyful Noise

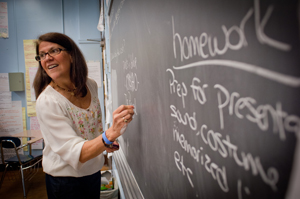

On a Monday morning at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, Ann Woodd-Cahusac Neary '74 prepares for her first class of the day, AP English Literature. She has brought chalk from home—teachers must supply their own—and arranges thrift-shop finds to serve as costumes and props for enacting scenes from Macbeth. Outside the frosted windows of the classroom is the school's perfect football field surrounded by a track.

A morning person who regularly wakes up at 4 a.m. to go to the gym before navigating the five highways between her home in Greenwich, Conn., and the Bronx, Neary stands at her classroom door to greet students as they come in from the hallway brimming with teenagers. “Good morning, gentlemen,” she says to two boys. “Oh, I really love that dress,” she tells a girl.

Just before eight o'clock, there are still some empty seats. The missing students, Neary supposes, are waiting to go through security. In a school rife with racial tension and 4,226 teenagers who need to remove shoes and belts before walking through a scanner, just getting in the door to school can be a challenge. And, after six years of teaching here, Neary knows how many other obstacles her students face in getting to class. She says that what they deal with is beyond what she can imagine dealing with and gives them “a huge amount of credit” just for showing up. One seat in the class will stay empty, though: a boy who lost his home at Christmas has disappeared. Neary had high hopes for him and is heartbroken.

Despite their burdens—drugs, abuse, being booted from their home or not being able to go to college because they have to care for their siblings—Neary's students do more than just show up: They are all senior honors students, and most will go to college in the fall. MIT, Vassar, Siena College, SUNY schools and others have accepted them, and they have options. Perhaps no one is more proud of them than the teacher they affectionately call Miss and Teacher Mom, who not too long ago considered her own options and chose to be at the front of a classroom instead of behind a corporate desk. For the first 30 years of her working life, Neary inhabited the world of retail, rising through the executive ranks from buyer for Lord & Taylor and a stint at Brooks Brothers to vice president of sales at Ghurka, a manufacturer of fine leather goods and accessories, and operations manager at Two's Company. Then, ten years ago, came the attacks of September 11. When the unthinkable happened, anything became possible.

Growing up in Greenwich, Conn., with an older sister and a younger brother, Neary was a good student at her high school of 3,000 students, but felt invisible. “I was kind of a lost-at-sea child; I was nothing special to anybody there,” she says. “I was very quiet and didn't get into trouble, so nobody noticed me.” Neary's guidance counselor thought a small college might be just the thing and suggested Colby Junior College for Women in New London, N.H. “I remember going on a lot of college tours and finally setting foot on the Colby campus and thinking, This is where I'm comfortable, I want to go here,” recalls Neary. “I loved everything about it: that it was in the woods and all girls; that it was small. I thought that was divine. I loved the college experience, when you realize you have the freedom to do whatever you choose.”

At orientation in Shepard Hall on her first day, Neary met Sue Brown Warner '74, also from Greenwich. They'd gone to the same school and never crossed paths, but they became close friends right away.

“We did so many goofy things,” says Warner. “We used to like to put on our 'footie' PJs and jeans and run down to Jiffy Mart to buy snacks in our matching shirts and socks.”

“It was a very safe feeling school; you could cross the street without looking,” Neary laughs. “And so it felt very natural. Sue and I were roommates senior year in Shepard and we've been connected at the hip ever since. Now she lives four miles away.”

A Liberal Studies major, Neary took mostly English classes with what she calls phenomenal teachers. “Professor Tom Biuso was a big favorite,” says Neary. “I credit him with my love of literature. I always loved reading, but he took us to unbelievable levels. We couldn't wait to go to class. And Dr. Hoffman, he was spectacular. I had great anthropology teachers, and I had the Curriers [Harold and Esther] for science. I took zoology, how cool is that? And we went sledding with our professors, which I thought was terrific.”

In the close-knit, supportive setting, Neary flourished, even ran for dorm president her senior year. “That was a remarkable experience because I was so shy. Then I had to run for election? That was so new to me, but what I got from Colby-Sawyer was the idea that you can do things. You can try things. You make a difference.”

That message, she says, came from everyone on campus: her “big sister” mentor, the RAs, even her peers. With the presidency—won in part, Neary thinks, because of the station wagons full of home-baked goods her mother delivered on visits—she branched out and became a tour guide.

“I was a poster child for the school because I just loved it so much. I don't think you could miss that if you were on a tour with me,” Neary says. “I loved everything about it. I loved the library—I love the new library more— the gym, the mountains. We even thought the dorms were beautiful.” After two years in New London and wearing a rut in I-89 North going back and forth to Hanover every weekend, Neary was ready to continue her education in a city on a co-ed campus, and the roommates headed to Boston College. Ann missed Colby-Sawyer and continued to date her Dartmouth boyfriend, Matt Neary, but earned her B.A. in English Literature and followed an interest in retail to Lord & Taylor, where she completed a training program to become a buyer. Prada replaced her college uniform of jeans, flannel shirts and combat boots for what Neary recalls as an exciting time meeting and working with designers. She also married a colleague and had her daughter, Emily Orenstein, who will be a junior at Colby-Sawyer this fall. Life was full, and full of change.

“When I was younger my mom was really busy with work,” says Emily, an English major who, like her mother, lived in Shepard Hall for two years. “I always wanted her around more. I remember one morning she was dropping me off at school and I said, 'You really should be teaching. I don't know what you're doing, but you should be a teacher.'”

Soul Food

When Ann bumped into Matt Neary again on the Metro North while commuting to Manhattan, it had been years since they had parted ways after their college romance. Matt, a periodontist, had three children from his first marriage, and Ann had Emily, from hers. They married and had twins, Paige and Mack, now 14 and champion water polo players—Ann's best friend Sue was again her labor coach and is the twins' and Emily's godmother. Ann traded the train ride to New York for a short drive to Ghurka and balanced work with raising her family and volunteering in her town, serving on various boards, and teaching Sunday School.

“It's important for me to love what I do,” Neary says of Ghurka, a family-owned business that at the time still created their leather goods by hand in Connecticut. But fine things lose their shine when towers crumble.

“I had an epiphany during the year following 9/11,” says Neary. “Matt and I were very involved in the work that went on after that. Matt is a forensics specialist and was down at the morgue once a week all night identifying remains. Through my church I volunteered once a week for a year at St. Paul's Chapel near Ground Zero for a 12-hour shift overnight. I helped feed the workers and did whatever I could. All those late nights made me think about what's important, and selling yet another fabulous business bag to a man so he looked good at a meeting really wasn't what I wanted to do anymore. What I really liked was working with kids. I like listening to them, hearing their stories. I like giving them a place where they can tell their stories.”

Neary, whose own father had changed careers to follow his dream to become an Episcopalian priest at age 68, took a hard look at the possibilities and decided to return to graduate school at age 50. With her family's support, she enrolled in Manhattanville College's accelerated teaching certification program in February and was ready to teach in September.

“When she went back to school we'd do homework together,” says daughter Emily. “It was fun to see her start teaching. She got really into it.”

Six years ago, teachers were in short supply, especially in New York City schools. When Neary completed some of her required observation hours at DeWitt Clinton High, she was “blown away” by the phenomenal, creative teachers she met and decided it was the school for her.

“I pursued an assistant principal until she had to hire me. I used all my business skills,” Neary laughs. “I called, followed up, sent my resume, kept asking if there was a job. I had a contract from New York City and they can place you anywhere they want, so I was getting anxious. When you're in business you don't take a job until you have the next one, so the fact that I could have a job but didn't know where, and might not know, until the day before school opened, was nerve wracking. Then DeWitt called and said they had a job for me in September. She asked when I could sign the papers. I was supposed to go on vacation that afternoon but I said, 'I'll come now!' I've been here ever since.” Neary has always excelled at everything she does, due to her boundless energy and enthusiasm, her friend Sue Warner says, but deciding to teach made perfect sense. “Ann was great at retail, but it didn't feed her soul. Teaching the kids at DeWitt Clinton has given her amazing, creative mind and caring nature a terrific—and very productive—outlet,” Warner says.

“She's so much happier and has made a huge contribution in a relatively short time in the profession.”

Where the Boys (and Girls) Are

“Teaching is very exciting. I like there to be something interesting every single day and that's where teaching mirrors the retail world,” says Neary. “I never know when I open the door what the kids are going to come in like. Your plans could go right out the window because someone's been burned out of their apartment or their mother got arrested over the weekend. They don't have dads. They come in with amazing stories.”

As Neary talks, her silver cross necklace catches the light and her charm bracelet jingles. One of the charms is engraved with the word Hope, an emotion that fuels her work as a teacher and which she senses and seeks to sustain in her students. Though their daily concerns often revolve around the most basic human needs for food, shelter and safety, Neary describes her students as warm, friendly, affectionate and wanting to do well.

“They really want to succeed. That's what gives me a lot of hope for them. Almost all of them will be first-generation college students and they have the ability, it's just a matter of whether they can sustain that knowledge to get to college,” she says. “Once they do, they'll see they can match other students. I like to think that we, as their teachers, provide an environment that's encouraging and makes them feel they're good at what they do.”

Ann Neary's classroom is not a quiet place. “I like active, joyful noise so my room tends to be noisier than some,” she admits. The students are comfortable with each other and her, but also respectful and engaged—especially when she assigns the task of acting out Macbeth in 32 seconds or less. They break into groups and rehearse. When she presents a kilt for Macbeth to wear, a student named Kevin hardly pauses before announcing, “I will wear it” to applause. Vigorous sword play and dramatic dropping to the floor ensue, and it becomes clear these students know this play.

Much of the physicality in Neary's classroom comes from her experience of teaching an experimental all-boys class based on Dr. Leonard Sax's research into how boys learn—he says you can't teach boys the same way you teach girls.

“In a mixed class you have to gear some lessons to how boys learn, and when they learn and what they're open to,” explains Neary. “If you only ask 'How do you feel about that poem?' they're not going to react because they don't want to talk about their feelings. But if you have a swordfight to represent that poem, they might get hooked.”

In 2008, Neary knew when boys dropped out—after ninth grade—and considered what she had seen in her lower-level reading class for freshmen, which students entered with reading levels as low as second and third grade.

“They drop out and they're failures at 14, because they can't read and write,” says Neary. “The social studies teacher says, 'Read this chapter on the Great Wall of China and the silk trade' and they're like, 'Read what?' None of the words make sense. So why would you want to come to school every day and be a failure? And be six feet tall and look like you're a grown man?”

Neary requested a group of incoming ninth grade boys and spent the summer learning how to teach them. She discovered, for example, that boys don't sit still. When school started, she gave one boy a clipboard on which to take notes while he paced. She put a Rubik's Cube in the hands of an excellent listener who simply needed something to fidget with. By March 2009, these boys had written poems of hope, apology, grief, despair and triumph that were published in the school's magazine, Magpie. Twenty-three of the 24 students passed and increased their reading levels by one or more grade levels. Though a success, the school moved on to other projects and the all-boys class experiment faded away. The lessons Neary learned didn't.

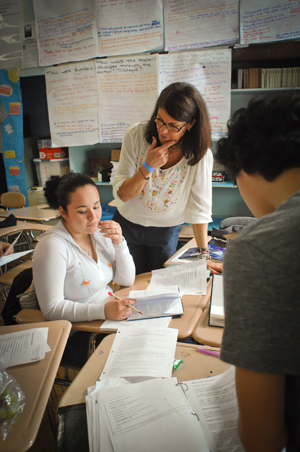

“That class totally changed the way I teach,” she says. “And because that was a relatively small class, it taught me—as Colby-Sawyer taught me—the importance of individual instruction. It's hard to do with a lot of children in your classroom, but the more time I can spend with each one, the better. It has a lot to do with noticing what each child can do.”

Senior Veronica Vergara says Neary's attention and concern don't go unnoticed. “Ms. Neary is a special person who cares about her students and where their studies can take them,” explains Vergara. “She gives us a lot of work, especially over the breaks, so we have time to digest what we read. Her main priority is helping us pass our exams. She knows how hard it is.”

Neary, who volunteered to join the two-year Measures of Effective Teaching project sponsored by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, also knows that there's more to education than studying for an exam.

“My students' lives here are sheltered even though it's inner-city New York,” says Neary. “They don't go into Manhattan, which is just a subway ride away. They stay within their block though they say they want to travel.”

To expand their horizons, Neary works with the Theater Development Fund, a nonprofit that provides a teaching artist in her classroom several times each semester. The ultimate benefit is free tickets to a Broadway show, and Neary overrides any hesitancy by mandating attendance.

“They don't understand the value because they don't know what theater is, but they will get a big old F if they don't take part so they all come and then they love it,” she says. “I spend the entire time watching them watch the show because they lean over the balcony in amazement at what a theater looks like, at the costumes and huge curtains. I push really hard for my kids to see theater.”

Faith, Hope and Love

When Neary calls her students “my kids,” it's indicative of what she has invested in them. She regularly provides snacks for her last class of the day because the students don't have lunch in their schedule, and last year she invited those who passed their AP exam to Greenwich to sail on her boat, The Wild Goose. Every day she goes home and thinks about what she could have done better or differently, and she carries her students with her.

“Oh, they live with me, they live at my house,” she says. “At the dinner table my children will ask, 'How's So-and-So, is her dad out of jail yet? And when I have some tragic tale they're like, 'Oh, no, not her, really?' They come home with me all the time. I think about them around the clock.”

That relationship doesn't end with graduation, either. A girl from Neary's first year of teaching still fills her in on college life. Students who graduated two years ago write to her about their search for summer jobs and hopes for the future. “Many of them are English majors, which makes me happy,” says Neary. “Some of them want to be teachers.”

When Neary, a member of the President's Alumni Advisory Council at Colby-Sawyer, returns to the campus where she learned from teachers who made a lasting impression, she loves what she sees. “I had a hard time swallowing the idea that boys should be here because it was such a wonderful women's college,” says Neary. “Now I like seeing men on campus, they seem happy and it's nice to have the diversity. I love listening to the professors; there are some amazing ones, as there were when I was there. I don't think that's changed, the caliber of instruction is excellent and if the students pay attention they'll get lifelong lessons. I love everything I see, though I know more things are needed—I love the idea of a new arts center. But what I see is all good.”

Fitting words from a woman who wears her faith around her neck and her hope around her wrist, and who gives away a little piece of her heart to her students every day.

- Kate Dunlop Seamans with photos by Michael Seamans (www.michaelseamans.com)