Colby-Sawyer College students in Writing 105 last fall participated in a contest for the best examples of research papers and essays completed for this class. The contest, sponsored jointly by the Wesson Honors and Liberal Education Programs, offers prizes of $125, $100 and $75 respectively. Three winners were selected (by Writing 105 faculty and Currents staff). In this issue of Currents, we feature one of the winning pieces, a research paper by first-year student Jaycee McCarthy.

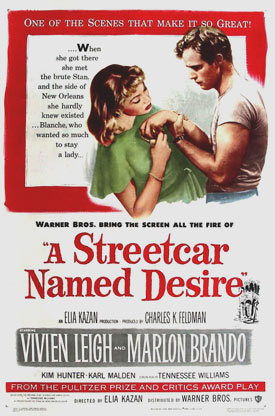

On The Lips: The Censorship of A Streetcar Named Desire

By Jaycee McCarthy '11

My junior year in high school was when I first encountered the work of Tennessee Williams while reading "The Glass Menagerie". I instantly became fascinated with his work and began to read other works by him, including "A Streetcar Named Desire". I enjoyed reading "Streetcar", but I wanted more of it. I rented the movie version, and enjoyed it even more than when I read it. I noticed some drastic changes from the play to the film, however, and wondered why they were made.

I ordered the extra second disc of "A Streetcar Named Desire" to learn all about the movie, the filming process, and its background. It was while watching that bonus disk that I realized why the changes were made from the play to the film - it was because of censorship. The censorship laws of the 1950s were strict, making it impossible for movies with adult topics, like "A Streetcar Named Desire," to be produced and approved without a fight from the Production Code Administration.

While I was reading and watching "A Streetcar Named Desire", I came across the typical stereotypes of a Pole in 1940s America. Having immense pride in being Polish, I was interested in learning of the culture and the stereotypes of a Pole in America. The film addressed Poles as Polacks and brute men. (Goska 410-414).

Blanche says, referring to Stanley, “He acts like an animal, has animal habits! Eats like one, moves like one, talks like one! ... Yes, there's something ape-like about him … Thousands of years have passed right by him and there he is – Stanley Kowalski – survivor of the Stone Age!” (Williams 323).

Stanley then stands up for his heritage, “Don't ever talk that way to me! 'Pig – Polack – disgusting – vulgar – greasy!' them kind of words have been on your tongue and your sister's too much around here!” (Williams 371). It only added to my enjoyment of the film that the main character was Polish and stood up for his heritage.

The play went through many drafts before becoming the final film product. The first draft was the actual play itself written by Tennessee Williams in 1947. It was immediately produced the same year on Broadway, directed by Elia Kazan and starring Marlon Brando and Jessica Tandy.

Then the play was taken from stage to screen in the 1951 movie, once again directed by Kazan, and starring Brando (again) and Vivien Leigh. Later, in 1993, the unedited, uncensored director's cut version was re-released, and production was stopped on the older, edited version. Since the 1951 film, "Streetcar" has also been made into two television movies and an opera.

In the summer of 1949, with the Broadway production still up and running (as it would until Dec. 14 of that year), producers and movie studios began looking to make the Broadway blockbuster into a film. However, everyone knew that censorship approval could make them alter "Streetcar" so badly, it would become “a box office failure, let alone an artistic mockery” (Schumach, The Face on the Cutting Room Floor 73).

The story is of Blanche Du Bois, an ex-Southern belle, whose fiancé commits suicide when Blanche finds out he is a homosexual. She is promiscuous in her hometown, and fired from her teaching job when she seduces a 17-year-old student. Later, while Blanche's sister is giving birth in the hospital, she is raped by her brother-in-law. Right there is enough to get the production companies worried: homosexuality, nymphomania and rape.

Studios turned to Joseph Breen, head of the Production Code Administration (PCA). The PCA was the primary governing body of all motion pictures and “no film… was to be released without a PCA Seal of Approval” (Lev 88). Paramount pursued the investigation quickly, but was discouraged when Breen told them that if they tried to make "Streetcar" into a movie, even references to rape and homosexuality would have to be eliminated (Schumach, The Face on the Cutting Room Floor, 73).

The Motion Picture Production Code was written in 1929, and many production companies of the late 1940s believed that it was outdated (Lev 87). The code had many principles which "Streetcar" violated, including: 1) No picture shall be produced which will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience shall never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin, and 2) Correct standards of life, subject only to the requirements of drama and entertainment, shall be presented” (Lev 87). "Streetcar" violated rule number one because at the end, viewers and readers have sympathy for Blanche even though she is a "wrongdoer."

It violated rule two because homosexuality and rape were not “correct standards of life." The production code based their laws on the Ten Commandments, and was actually written by a Jesuit priest (Lev 88).

The code also says, in Section III, regarding sex, that “No film shall infer that casual or promiscuous sexual relationships are the accepted or common thing” (Schumach, The Censor As Movie Director, 36). This is a problem, seeing as Blanche is promiscuous. Another problem that arises is in regards to the “Special Subjects, Section IX,” which states that “bedroom scenes must be treated with discretion and restraint and within the careful limits of good taste” (Schumach, The Censor As Movie Director, 36). The only bedroom scene in the script is a rape, which for sure is not within the limits of good taste.

Paramount, the first production company to attempt the transition from page to screen, wondered why the play could be produced on stage before an audience, but not through film. Breen's answer was that “...the provisions of the Production Code are quite patently sat down in knowledge that motion pictures, unlike stage plays, appeal to mass audiences; to the mature and immature, to the young and the not-so-young. Because these motion pictures are exhibited rather indiscriminately among all kinds of classes and audiences” (Schumach, The Face on the Cutting Room Floor, 73).

Basically, the play was perfectly suitable as a theatre production because of the different standards between film and theatre. The censors viewed their job as a responsibility to the public to show only high-class, quality films acceptable to all ages. Granted, there was no official rating system at that time (as we have now with R, PG-13, PG, etc) so anyone, as long as they had the money, could buy a ticket to any show they chose. The PCA believed that it was their responsibility to censor the public.

When Paramount backed down, Warner Brothers, led by Charles K. Feldman, decided to take on the risky task of making "A Streetcar Named Desire" into a film - a process that soon turned into a major headache. Feldman collaborated with Kazan to direct the film, and the screenplay was to be written by the author himself, Tennessee Williams.

Kazan was conscious of the ways in which working in Hollywood involved a “conflict between notions of film as art and film as entertainment” (Lev 78). He was worried about becoming involved, but eventually gave in and decided to direct the film. While Kazan was in the brainstorming process, he decided that he would modify the play to make it more cinematic.

However, as time went on, he changed his mind to make the film “adhere to the play's original design” (Pauly 130). Three quarters of the film ended up taking place on a set no bigger than a Broadway stage, making it as original as possible.

Williams created a screenplay that was accepted by Warner Brothers and Kazan, and which included 68 major and minor changes from the Broadway version (Pauly 131). However, the trouble would be having the censors at the PCA accept it. When the censors got a hold of it, at first, they just eliminated some of the "damns" and "hells" (Schumach, The Face on the Cutting Room Floor, 74).

Then Breen of the PCA brought up the deeper topics, such as homosexuality. In the original script, Blanche says the following lines, in regards to her homosexual fiancé, “Then I found out, in the worst of all possible ways. By coming suddenly into a room that I thought was empty – which wasn't empty, but have two people in it … the boy I had married and an older man who had been his friend for years” (Williams 354).

Kazan, willing to lose this battle in the hope of winning others, agreed to eliminate the homosexuality reference. Kazan said, “I wouldn't put the homosexuality back in the picture, if the code had revised it last night and it was now permissible. I don't want it. I prefer debility and weakness over any kind of suggestion of perversion” (Schumach, The Face on the Cutting Room Floor, 74). Kazan believed that saying the man was a homosexual, almost gave too much away. He would rather let the viewers decide. Williams sat back and watched his art being torn into shreds.

Breen then went after a second topic, insisting that the rape be thrown out of the film. Williams finally spoke his mind and said he would not allow the rape to be removed. “'Streetcar' is an extremely and peculiarly moral play, and the rape of Blanche is a pivotal, integral truth within it. Without it, the play loses its meaning, which is the ravishment of the sensitive and delicate by the savage and brutal forces of modern society.

"It is a poetic plea for comprehension... we are fighting for what we think is the heart of the play, and when we have our backs against the wall – if we are forced into that position - none of us are going to throw in the towel! We will use every legitimate means that any of us art his or her disposal to protect the things in this film which we think cannot be sacrificed, since we feel that it contains some very important truths about the worlds we live in (Pauly 132)." Williams was not going to let his work, after he made so many changes already, be torn up any more.

Breen states in Schumach's The Face on the Cutting Room Floor that "Streetcar" “made us think things through. We realized it was possible to treat rape on the screen” (72). Breen finally caved and allowed it, but he wanted the ending changed. The play ends with Stella refusing Blanche's accusations of rape. And Stanley and Stella watch as her sister is escorted out of the house to an insane asylum. After Blanche is gone, Stanley comforts Stella saying 'Now, baby. Now, now, love,” (Williams 419) and slides his fingers in the opening of her blouse. It is assumed that life is back to normal (Schumach, The Face on the Cutting Room Floor, 75).

Breen needed the husband to be punished for his crime. Williams reluctantly agreed on an alternating ending, having Stella run out of the house and say to her baby after Blanche is taken away, “We're not going back in there. Not this time. We're never going back. Never, never back, never back again” (Brando and Leigh). Breen agreed with William's new ending that was forced by the Production Code or the producers would face the consequence of the film not being released.

Williams and Kazan, having finished the censorship process for "Streetcar" (or so they thought), went on to other works. However, when the Legion of Decency got their hands on it, more revisions were demanded. The Legion of Decency was a group of devout Catholics who Other Christians would view movies, or not, based on their LOD rating.

The LOD rating system was the only one used in the late 1940s, but was unofficial and not a requirement for a movie to be produced. Their ratings were as follows: A-I for Morally Unobjectionable for General Patronage, A-II for Morally Unobjectionable for Adults, B for Morally Objectionable in Part for All, and C for Condemned (Lev 95).

The LOD threatened to give "Streetcar" a C rating. Granted, LOD approval was not necessary to release a film, but a bad rating could affect the profits. The C rating would keep many Catholics away, and even raise the possibility of the film being banned in major Catholic cities. The rating “could block bookings in major theatres, especially in cities with heavy Catholic populations” (Lev 30). So, the negotiations began. Feldman asked Kazan to meet with the Legion and he did so, though unenthusiastically.

Kazan remembers the Legion as a group of patronizing, soft-spoken men. They weren't asking him to do anything; they were just telling him what they thought. Kazan and Williams told Feldman they weren't going to make any of the changes the Legion suggested and stormed off. Kazan and Williams then went back to work, looking forward to the release of "Streetcar" (Schumach, The Face on the Cutting Room Floor 77).

However, there was one aspect of the censorship process that both Williams and Kazan had not considered. “The Right of the Final Cut” was the studio's right to cut portions of films without the writer or director's consent. Warner Brothers, truly fearful of the Legion of Decency's C rating and failure at the box office, gave in. They made 12 cuts, as suggested by the LOD, over four minutes of footage.

The cuts included the words “on the mouth” from Blanche's line “I would like to kiss you soft and sweetly on the mouth” when a young collector comes to the Kowalskis' flat. Also, the opening to the scene was changed from a slow dissolve to a straight cut, to cover Blanche's slight moans and her raising her leg high. (Lev 32). Also, as the boy goes to leave, Blanche's line, “It would have been nice to keep you, but I've got to be good – and keep my hands off children,” was cut.

Also cut from the 1951 release were lines that Stanley says while Blanche is flirting with him. He says, “You know, if I didn't know that you were my sister's wife, I would get ideas about you.” It was removed because it alluded to the referencing of rape and Stanley and Blanche's adulterous relationship. (Lev 35)

Also, some close-ups were deleted because they allegedly indicated that Stella's relationship with her husband was too carnal. Stanley's line, before he rapes Blanche, “You know, you might not be bad to interfere with” was also removed (Schumach, The Face on the Cutting Room Floor).

While the Legion was watching the film, they could only focus on one thing. As soon as the word desire is seen on the streetcar [in the opening scene] the entire tone of the picture is 'desire' (physical desire)” (Leff 30). From that moment on, the LOD became infatuated with the concept of desire. It didn't help that Blanche pronounced 'desire' as three syllables 'dee-sire-uh' (Leff 30). The way she pronounces it makes it more sexual and even less appealing to the LOD.

Kazan was infuriated when he heard that cuts were made to his final product. He said that “Warner's just wanted a seal. They didn't give a damn about the beauty or artistic value of the picture. To them it was just a piece of entertainment. It was business, not art. They wanted to get the entire family to see the picture. They didn't want anything in the picture that might keep anyone away. At the same time they wanted to be dirty enough to pull people in. The whole business was an outrage” (Schumach, The Face on the Cutting Room Floor, 78).

Kazan was upset because they had not told him about these cuts. He had known about the LOD's possible C rating, but did not think it mattered. On the other hand, Warner wanted everyone to buy a ticket, regardless of whether or not the changes ruined the film's artistic value.

Despite losing some battles of censorship, Kazan had won the war. When the film was released, it proved the censors wrong and was a huge success. The public flocked to it, and it was “roundly proclaimed a masterful adaptation of William's play” (Pauly 136). The film also won numerous awards, including Academy Awards for Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Karl Malden), Best Actress in a Leading Role (Leigh), Best Actress in a Supporting Role (Kim Hunter), and Best Art Direction – Set Decoration, Black-and-White.

Other nominations included Best Actor in A Leading Role (Brando), Best Picture, and Best Writing, Screenplay. “'Streetcar' was the first film to win the seal of approval from the movie industry's censors despite the conviction of the guardians of the movie code that this was not a “family picture” (Schumach, The Face on the Cutting Room Floor, 72).

In 1993, with the release of the unedited, uncensored version, film critic Roger Ebert was shocked at the discrepancies between the versions and said the changes “took away much of [the film's] impact” (Heins 287). "A Streetcar Named Desire" became a giant milestone in movie-making history.

The Legion of Decency's influence =declined in the 1950's “when it became clear that Legion objections might not hurt a film at the box office” (Lev 95) as it did with "Streetcar." On Dec. 11, 1956, a revised version of the Production Code was released, thanks to the help of Elia Kazan and Streetcar. "A Streetcar Named Desire" was risqué, but proved to be what the public wanted to see, in an era where change was happening everywhere.

Jaycee McCarthy '11 of Saugus, Mass., intends to major in English at Colby-Sawyer College. His interests include acting, music and writing. He is president of the 2011 Class Board and is currently involved in theatre.

Works Cited

"A Streetcar Named Desire: The Original Director's Version." Dir. Elia Kazan. Perf. Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh. 1993.

Goska, Danusha V. "The Bohunk in American Cinema." Journal of Popular Culture June 2006.

Heins, Marjorie. "Forbidden Films". New York: Checkmark Books, 2001. Leff, Leonard J.

"And Transfer To Cemetery." Film Quarterly, March 2002: 29-37.

Lev, Peter. Transforming the Screen, 1950-1959. New York: Charles Scrbiner's Sons, 2003.

Newman, Bruce. "Williams: From Stage to Screen: NEW SET REVEALS HAND OF HOLLYWOOD CENSORS." San Jose Mercury News 4 May 2006.

Pauly, Thomas H. An American Odyssey. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1983.

Schumach, Murray. "The Censor As Movie Director." New York Times 12 February 1961: 15, 36, 38.

The Face on the Cutting Room Floor. New York: Da Capo Press, 1974.

Shanley, John P. "Tennessee Williams on Television." New York Times 13 April 1958: 13.

Williams, Tennessee. "A Streetcar Named Desire." New York: New Directions, 1971.